Deep Blue Dreams (Part 1): Thor Heyerdahl, Tiki Culture, and Postwar America’s Love Affair with Oceans

Once Upon a Time in Postwar America… A voyage across the Pacific Ocean by Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl captured the imaginations of millions of Americans and launched a nationwide craze…

Dear Reader,

Welcome to a new adventure on Postwar Pop! I'm thrilled to invite you to Deep Blue Dreams, a journey through the seas of Postwar American culture, where we'll explore the fascinating relationship between the American imagination and the vast, mysterious oceans that captured it.

In the decades following World War II, Americans found themselves increasingly drawn to the allure of the sea. From the late 1940s through the 1970s, oceans became a powerful symbol in the nation’s collective consciousness — representing adventure, discovery, and the unknown.

This series will dive into the various ways that oceans permeated Postwar American popular culture and shaped the country’s national identity. Through these posts, we'll examine how the vastness of the oceans mirrored America's expanding horizons, how underwater exploration paralleled the Space Race, and how sea-themed popular culture reflected the hopes, fears, and dreams of a nation in transition.

So… grab your figurative snorkel and prepare to submerge yourself in this intriguing aspect of postwar American history. Together, we'll uncover the currents that shaped America’s cultural landscape and continue to influence us today.

Anchors aweigh!

Andrew Hunt

“In this machine age, the spirit of adventure has a hard time thrusting its way through dials, gauges and blueprints; there are so few places left on the face of the earth where man has not already penetrated with his guns and trucks. It is difficult to seek out old-style adventure anymore.”

– Norman Cousins (on Thor Heyerdahl), 1950[1]

“It was that fantastic feeling of peace in the middle of a vast ocean. There was no noise except the gentle lapping of the seas against the logs. It was a feeling of being suspended in space.”

– Thor Heyerdahl, 1951[2]

Kon-Tiki: A Postwar Sensation

In the early years of Postwar America, few nonfiction books captured the public imagination as much as Norwegian explorer and writer Thor Heyerdahl’s The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas, first published in England and the United States in 1950. At its core, Kon-Tiki is an incredible adventure narrative. Six men, a homemade raft made of balsa logs, 101 days at sea across thousands of miles of the Pacific, battling storms, encountering sharks, all to try to prove a controversial theory — that ancient Polynesia could have been populated by people from Peru, rather than from Asia, as was traditionally believed. It is a gripping, against-all-odds tale of human courage and endurance and it reads like a page-turning action novel. The stakes were high in this instance. Some experts insisted that Heyerdahl and his crew were on a suicide mission.

But — spoiler alert — the ending in this case was a happy one for Heyerdahl and crew. By the mid-1950s, countless bookshelves in houses across the United States contained a copy of The Kon-Tiki Expedition. The book remained on American bestseller lists throughout 1951.[3] The years that followed its publication saw the continued rise of mass media, especially radio, popular magazines, newsreels, cinema, and the nascent but growing medium of television. The dramatic nature of the Kon-Tiki expedition made for compelling content across all these platforms, allowing the story to reach a vast audience quickly.

Kon-Tiki (as it was known for short) took America and other parts of the world by storm, exceeding Heyerdahl’s highest expectations. It was translated into multiple languages, breaking records internationally. As literary critic Fanny Butcher noted shortly after it arrived in North American bookstores in 1950:

On a table near the author were copies of a few of the foreign editions of Kon-Tiki, but not all of those in the 19 languages in which it now appears. They include such rarely read ones as Indonesian and Croatian, and I hear that there is even one in, of all things, Esperanto. Probably no book in modern times has had such a wide and enthusiastic reading public. When I asked Mr. Heyerdahl how many copies had been sold in [his native] Norway, he said that the last figure he knew of was 60,000. When you realize that the population of Norway is only 3,000,000, that must mean that practically everybody in the country is reading Kon-Tiki.[4]

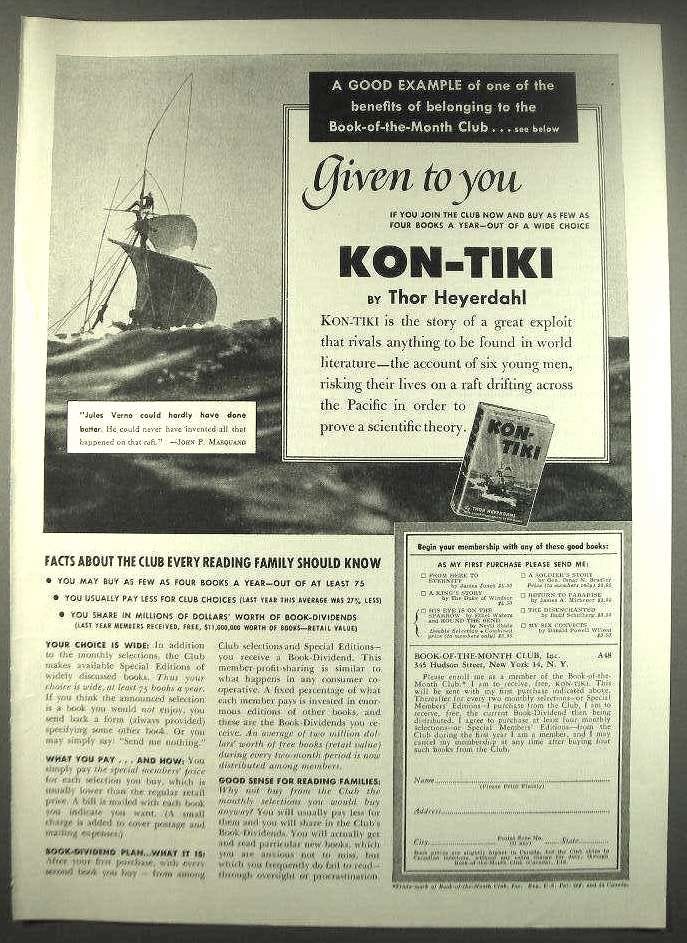

Adding to Heyerdahl’s fortunes, the popular Book-of-the-Month Club (BOMC) played a key role in the promoting the book. Being selected by the BOMC guaranteed a massive distribution and exposure to millions of American households. The BOMC was enormously influential in the Postwar era, acting as a trusted curator of popular and significant books, and its endorsement alone could propel a book to bestseller status. A BOMC ad from 1951 for Kon-Tiki explicitly used the line, “A good example of one of the benefits of belonging to the Book-of-the-month club.”

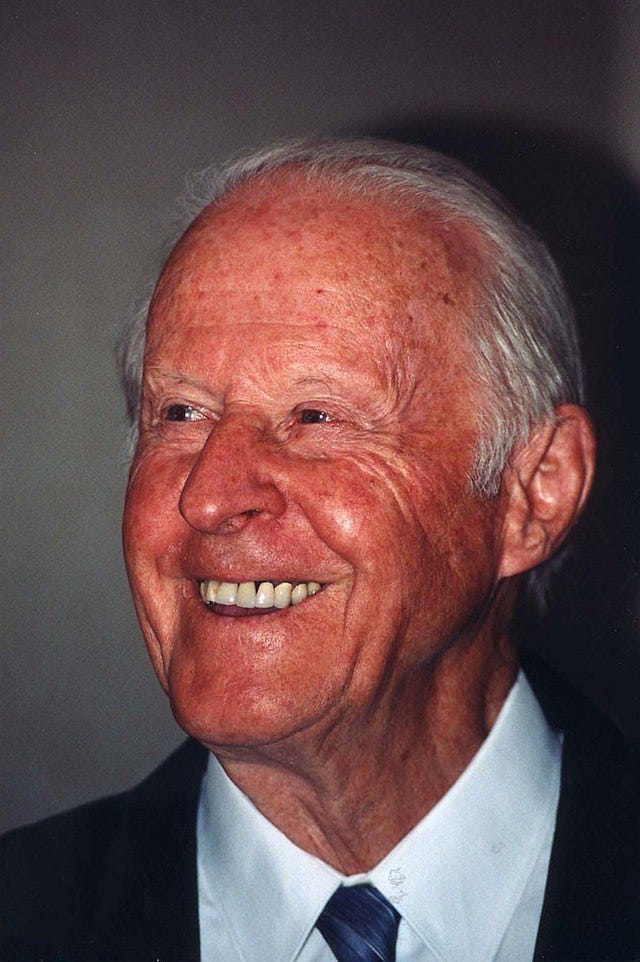

The Kon-Tiki Expedition ended up being a cultural phenomenon, released in North America to coincide with showings of Heyerdahl’s widely viewed 1950 Kon-Tiki documentary film, which netted an Academy Award for Best Feature Documentary. Its success owed entirely to Thor Heyerdahl (1914-2002), anthropologist, explorer, writer, ethnographer — man of many hats — who set out after World War II to determine whether he and a small crew could sail across the Pacific from Peru to the Tuamotu Islands, French Polynesia, using a raft built of thick balsa wood logs and other materials native to South America.

The original Oscar-winning documentary Kon-Tiki (1950) is available for viewing on YouTube. It is a fascinating glimpse into the voyage that captured the imagination of people around the world, especially in the United States.

The Odyssey of Thor Heyerdahl

Thor Heyerdahl, son of a respected Norwegian brewery owner, grew up in Larvik, Norway. As a child, he created a museum in his own house, built around the family’s beloved pet viper. Visitors came from far and wide to see the ambitious young lad’s displays. He later attended the University of Oslo, where he studied geography and zoology. Always intellectually driven, he first journeyed to French Polynesia in 1937 with his first wife, Liv, and he fell in love with the history and lore and culture of the archipelago.[5]

Heyerdahl became obsessed with the idea of Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic travels between South America and islands in the Pacific, especially Polynesia. For a time, World War II sidetracked his studies of the Pacific islands, and he turned his focus to the Norwegian anti-Nazi resistance movement. After the war, he shifted his attention back to Polynesia.[6]

He decided sometime during 1946 that he was going to set sail across the Pacific in a craft made of materials from Peru, to see if he could reach French Polynesia. He began assembling a crew of trusted friends and associates to aid in the endeavour. He told an interviewer in 1951: “Scientists laughed at me when I said I wanted to make the voyage in a balsa wood raft. They said that balsa wood absorbed water and that the raft would sink. But I was to discover later that balsa, cut from Peruvian jungles in the rainy season, was impregnated with sap and resisted water.”[7]

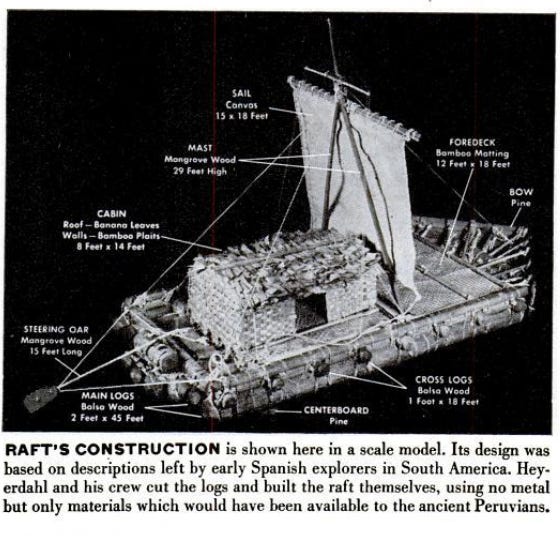

Heyerdahl and his crew built their raft in 1947 — made of giant balsa logs tied together with ropes — and they constructed a bamboo hut to house the crew. They launched their voyage from Peru’s shores on April 28, 1947. As one contemporary account at the time noted: “None of them was a seaman and even seamen didn’t know the purpose of some of the features of the raft. Most mariners doubted that the craft would hold together under the strain of a long ocean voyage, or that the balsa logs would stay afloat when they became waterlogged.”[8]

Heyerdahl called the raft Kon-Tiki, after a so-called “white sun god” that he first heard of Fatu-Hiva, the southernmost island of the Marquesas Islands. On board their vessel with Heyerdahl and his crew of five were sophisticated radios, some of them supplied by the United States Department of Defense, and other modern-day navigation equipment to help guide the voyagers. The men lived on fish and aquatic plants pulled from the Pacific Ocean, and they sailed through blinding sun and pouring rain. They arrived at their destination in August thinner, tanner, and with more facial hair, but otherwise in good shape.

Heyerdahl became an instant celebrity — literally overnight — because of his highly publicized “exploration” Ruggedly handsome, he embodied the archetype of the daring, self-reliant explorer. In an era of increasing technological complexity, Heyerdahl's decision to prove his theory by recreating an ancient voyage using primitive materials struck a chord with people around the world. He put his life on the line, displaying an unwavering commitment to his ideas and a trust in ancient wisdom and natural forces. His “man against the elements” narrative resonated deeply, deeply impressing ordinary people who learned of his journey.

He also happened to be a damn good writer. Here is a passage from his book that is equal parts vivid and memorable:

On that particular evening we sat, as so often before, down on the beach in the moonlight, with the sea in front of us. Wide awake and filled with the romance that surrounded us, we let no impression escape us. We filled our nostrils with an aroma of rank jungle and salt sea and heard the wind's rustle in leaves and palm tops. At regular intervals all other noises were drowned by the great breakers that rolled straight in from the sea and rushed in foaming over the land till they were broken up into circles of froth among the shore boulders. There was a roaring and rustling and rumbling among millions of glistening stones, till all grew quiet again when the sea water had withdrawn to gather strength for a new attack on the invincible coast.[9]

As this passage reveals, beyond his academic pursuits and writing abilities, Heyerdahl was a natural raconteur and showman, and an effective communicator. The book he sat down to write about his expedition shined with vivid prose. He possessed the ability articulate his adventures and theories in a way that captivated a mass audience. He became a popular lecturer, widely disseminating his stories and engaging directly with the public. Audiences loved him. Crowds at sold-out venues routinely gave him standing ovations wherever he went.

In the Shadow of a Voyage

Heyerdahol had critics, for sure. Naysayers insisted he was publicity-hungry; that his theory was full of holes, and his voyage proved nothing; that he was in it for fame and money rather than advancing a discoveries. Academics openly scoffed at The Kon-Tiki Expedition, questioning its validity and the usefulness of the author’s methodology, arguments, and conclusions.

Later generations of scholars accused Heyerdahl of trafficking in racist assumptions about Polynesians and Peruvians.[10] As author Andrew Lawler noted in 2010: “Heyerdahl thought that the original seafarers came from the Middle East via South America, where they bestowed civilization on dark-skinned peoples before setting off across the world's largest ocean.”[11] However, over time, Lawler adds, the scholarly community began to accept the “once-heretical notion” of “seafaring Polynesians trading with ancient South Americans,” a view that in by the 21st Century has been gradually inching toward “accepted wisdom.”[12]

Despite his detractors, Thor Heyerdahl enjoyed a distinguished career as an explorer, ethnographer, and author, and his later books routinely appeared on bestseller lists. But none reached the same astronomical level of commercial success, cultural impact, or public fascination as Kon-Tiki. His later book The Ra Expeditions (1971) — detailing his voyages across the Atlantic in the papyrus reed boats Ra I (1969) and Ra II (1970), to prove that ancient Egyptians could have crossed the Atlantic to the Americas — sold as briskly as Kon-Tiki and led to another documentary film. But The Ra Expeditions lacked the sheer wallop of Kon-Tiki.

The demands of maintaining a public persona often took Heyerdahl away from his family for extended periods. He was married three times, and he had three daughters. Heyerdahl continued to tirelessly write books, make documentaries, and lecture around the world until his death in 2002. His third and final wife, French actress Jacqueline Beer, served as Chair of the Thor Heyerdahl Research Centre in Aylesbury, England, after he died.

Kon-Tiki and the Rise of Postwar Tiki Culture

Kon-Tiki — the book and the film — and the interest surrounding Heyerdahl and his life, revealed the Postwar era’s burgeoning fascination with “last frontiers.” Oceans, in particular, represented vast, largely unexplored territories on Earth. People were ready for real-life stories of adventure and discovery after years of war. By attempting to show the world how an ancient journey might have happened, Heyerdahl was not “discovering” an unmapped land, but he was rediscovering the forgotten capabilities of humanity and the deep mysteries of the ocean itself. Through his actions he taught that even in a seemingly mapped-out world, there were still vital questions begging for exploration, and daring feats yet to be undertaken.

Heyerdahl's expedition tapped into a widespread public curiosity about the unknown — and the place of human beings in that mysterious realm. Heyerdahl attempted to demonstrate that oceans, far from being insurmountable barriers, could be pathways for peoples ancient and modern, linking continents in ways previously unimagined. His work cultivated a sense of wonder about the sea’s power and potential.

The huge boost to the book provided by the Oscar-winning documentary Kon-Tiki provided a visual account of the incredible journey, bringing the adventure to life on the big screen for a wider segment of the population — a kind of cinematic CliffsNotes for the book. The combination of a compelling book and a memorable movie created a critical cultural moment in the imagination of millions of people.

Coming out of World War II, people hungered for narratives celebrating human achievement, ingenuity, and peaceful exploration. Kon-Tiki offered a refreshing contrast to the grim realities of bloody global conflict and newly emerging Cold War anxieties. It presented a story of international cooperation, spotlighting a crew that was Norwegian and Swedish, which received aid from the United States Army and Peruvian authorities.

This was, in every sense, a shared human undertaking.

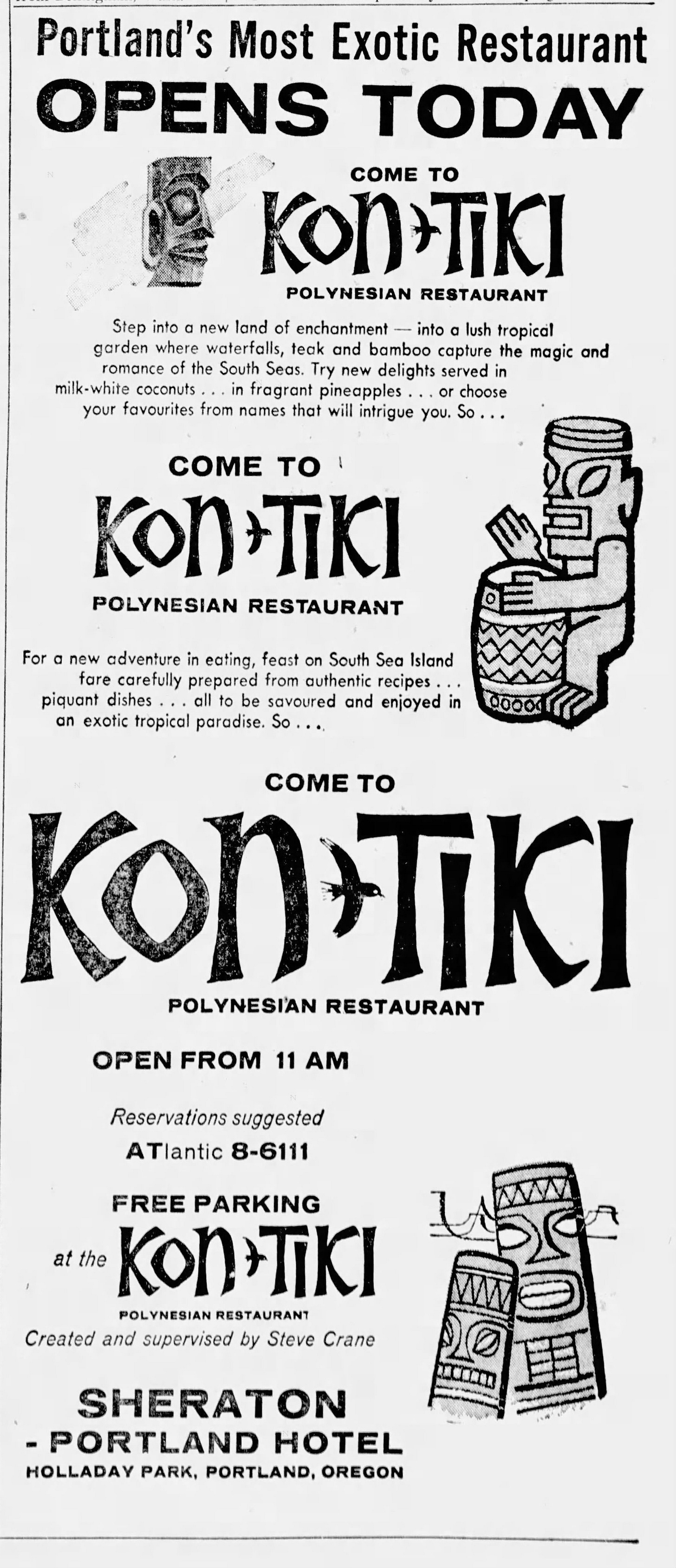

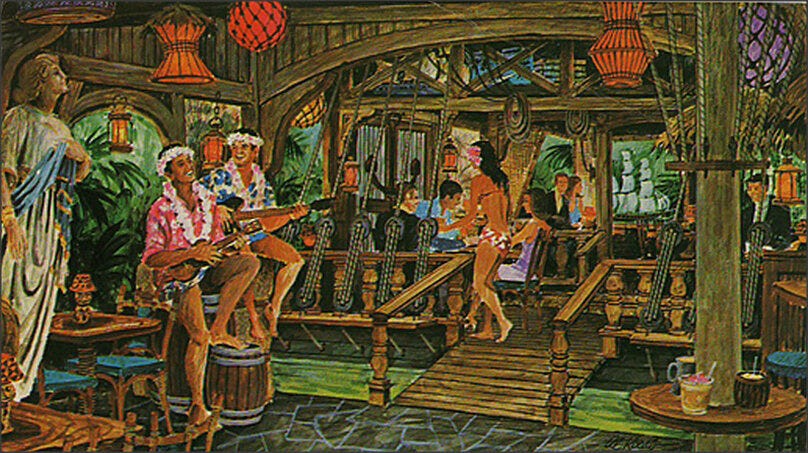

And let’s not forget the massive nationwide Tiki Craze that followed Kon-Tiki. Shrewd entrepreneurs who understood which way the wind was blowing capitalized on the fame of Kon-Tiki. “Tiki” bars and restaurants, which had a marginal presence in California since the 1930s (thanks to the efforts of early promoters like Donn Beach and Victor Bergeron), exploded in popularity after Heyerdahl’s trek. Establishments explicitly named Kon-Tiki Ports, opened by businessman Steven Crane in partnership with Sheraton Hotels, leveraged Heyerdahl’s fame. These places contained Tiki carvings, thatched roofs, tropical drinks (remember the tiny umbrellas?), and an overall exotic “South Seas” ambiance.

Moreover, Heyerdahl’s influence could be felt inside Disneyland's Enchanted Tiki Room, a popular attraction at the theme park that featured Disneyfied versions of Polynesian art, music, and general exoticism — all building on a romanticized Postwar American celebration of oceans and imaginings of South Pacific island living. Coincidentally, so-called “Tiki Torches” — which proliferated in American suburbs — provided an exotic glow that lit suburban backyards and flickered in poolside barbecues. Ubiquitous Tiki Torches in the 1950s and 1960s spoke to the desire for affordable, accessible escapism and a touch of tropical glamour in everyday life.

Tiki idols. Tiki masks. Thatched huts. Tiki torches. Pineapple upside-down cakes. Coconut palm trees. You could not miss the Tiki craze in the 1950s, even if you desperately wished to avoid it.

And constantly playing in the background was an “Exotica” music soundtrack, performed by the likes of Les Baxter and Martin Denny. These lush, atmospheric soundscapes blended traditional orchestral elements with “exotic” instruments and sounds (jungle bird calls, tribal drums, ethereal vocals, and recordings of ocean waves). Exotica music was explicitly designed to transport listeners to faraway, idealized tropical locales, helping to set the ideal mood in Polynesian restaurants and lounges and suburban get-togethers.

Composer, musician, and conductor Les Baxter (1922-1996) specialized in “Exotica,” a type of music that sought to replicate the experience of being in exotic locations, such as the Polynesian Islands. This track, “Jungle River Boat,” turned up on his 1951 album Ritual of the Savage, widely regarded as a pioneering early work in Exotica music.

The Tiki craze – and the accompanying Americanization of Polynesian, Melanesian, Micronesian, and Hawaiian culture – revealed how deeply ingrained and multifaceted the “oceanic obsession” was in Postwar American popular culture. Before the space race came to dominate the public imagination (though it was nascent in the 1950s), oceans represented a vast, unexplored “final frontier” on Earth. They held mysteries, potential resources, and untold wonders.

Playing a vital role in starting this nationwide love affair with oceans in the United States was Norwegian man and his voyage across the Pacific in 1947. The world had recently emerged from the most devastating conflict in modern human history. Millions had died, economies were shattered, and societies were still reeling from the trauma. Such horrors fuelled a collective yearning for peace, normalcy, and a break from the grim realities of warfare.

Answering these yearnings, Kon-Tiki offered a narrative that was the antithesis of war — a tale of peaceful exploration, human ingenuity, and a return to fundamental, almost primal, challenges that were thought to be lost to modern civilization. Kon-Tiki capitalized on this fascination with earthly exploration at a moment in time before the Space Race shifted focus to the heavens. In essence, Thor Heyerdahl’s 1947 voyage allowed Kon-Tiki to tap into a collective Postwar psychological need for optimism, adventure, and proof of human resilience.

It was the right story, at the right time, told by the right person.

NOTES

[1] Norman Cousins, “‘Kon-Tiki’ Recaptures Spirit of Adventure,” Newark Star Ledger, December 17, 1950, 76.

[2] “The Kon-Tiki Crew of Adventurers: Thor Heyerdahl Gambled on a Theory and Won,” Boston Globe, May 11, 1951, 24.

[3] Fanny Butcher, “The Literary Spotlight,” Chicago Tribune, January 6, 1952, 172.

[4] Fanny Butcher, “The Literary Spotlight,” Chicago Tribune, December 17, 1950, 126.

[5] The precise date of Thor Heyerdahl’s first trip to the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia is challenging to determine. Some sources list it as 1936, others 1937. I am slightly more persuaded that it happened in 1937, although it was hard to pin down a definitive date, and it may very well have occurred in 1936.

[6] For a decent biography of Thor Heyerdahl, Christopher Ralling, The Kon-Tiki Man: Thor Heyerdahl (London: BBC Books, 1990).

[7] Robert H. Prall, “Scientist Who Led Kon-Tiki Voyage: Thor Heyerdahl a Modern-Day Viking Who Made Expedition to Back Theory on Origin of Pacific Peoples,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 11, 1951, 51.

[8] Gideon Seymour, “Tops in Sea Adventure Tales; Six Cross the Pacific on a Raft,” Minneapolis Star-Tribune, September 17, 1950, 74.

[9] Thor Heyerdahl, The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas (New York: Pocket Books edition, 1956), 11.

[10] For example, see Scott Magelssen, “White-Skinned Gods: Thor Heyerdahl, The Kon-Tiki Museum, and the Racial Theory of Polynesian Origins,” TDR: The Drama Review, Vol. 60, No. 1 (Spring 2016), 25-49

[11] Andrew Lawler, “Beyond Kon-Tiki: Did Polynesians Sail to South America?,” Science, Vol. 328, No. 5984 (11 June 2010), 1344-1347.

[12] Ibid., 1347.

Mormons, seeking legitimization of the church’s belief that this continent’s indigenous people migrated from Asia on balsa rafts, enthusiastically applauded Heyerdahl’s adventure!

My parents had many tiki torches all around the patio and throughout the back yard! Great addition to Substack - I look forward to more Deep Blue Dreams!