Anatomy of an Inferno

The enormous Bel Air fire of 1961 foreshadowed the much larger and more destructive Los Angeles wildfires of today

PLEASE NOTE: This article also includes an audio version of the author reading the article (above).

NOTE TO READERS: Even though Dispatches from the Blue Room focuses primarily on the history of American popular culture, I’ve long been fascinated by the November 1961 Bel Air fire in Los Angeles, and I thought it would be appropriate – given the devastating magnitude of the wildfires in Southern California still happening as I write this – to focus on the huge ’61 fire and its impact on the community. It is a slight departure from what I usually write here, but I hope you find it informative, nonetheless. Next week, I will publish the second article on a series I’m writing on Gidget and its cultural impact. For now, let’s turn our attention to the 1961 Bel Air fire. – AH

The California wildfires currently burning around the state – especially the massive blazes spreading across the Santa Monica Mountains overlooking Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley, and the gigantic Eaton fire to the east that has ravaged large parts of Altadena – have been equal parts horrifying and apocalyptic to behold. Film footage and photos, on television and online, show a churning sea of orange flames leaping into the smoke-filled skies. Thousands of heroic personnel are battling the fires on the ground, while flying water tankers roar overhead dropping water on the frightening inferno.

“People are literally fleeing. Kids have lost their schools. Communities have lost their churches. Families have lost their homes. Some have even lost their lives,” said California Governor Gavin Newsom in a Tweet on January 8, 2025.

The scope of the wildfires has been nothing short of staggering. And completely shocking.

Southern California has long history of harrowing wildfires. And although the current fires are much larger in scale than past wildfires, the long history of how Californians have dealt with the threat of large-scale infernos is as fascinating as it is heartbreaking.

And that history can sometimes illuminate conditions in the present.

The parallels between the 2025 L.A. wildfires and the November 1961 Bel Air fire are striking. In addition to the two fires happening in close proximity to each other, both of them were fanned by the treacherous Santa Ana winds. These hot, dry winds blow from the desert towards the coast, dramatically increasing fire risk.

They were particularly strong on November 6, 1961, the day the huge Bel Air fire broke out, fanning the flames on a rapidly expanding trajectory.

The date was Sunday, November 5, 1961, and the world was changing . . .

President John F. Kennedy met with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in Newport, Rhode Island, to discuss relations between the two nations.

Tensions simmered at hot spots around the world, including South Vietnam and the Congo, where violent conflicts were exploding between ruling governments and guerrilla insurgents.

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev warned the world that his government would step up Soviet atmospheric nuclear tests if the United States was planning to do likewise.

And moviegoers flocked to theatres and drive-ins to see such films as Breakfast at Tiffany’s, The Hustler, Come September, Back Street, By Love Possessed, Splendor in the Grass, King of Kings, and The Devil at 4 O’Clock. Meantime, TV viewers watched popular Sunday night shows like Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color, Bonanza, Dennis the Menace, the Ed Sullivan Show, I’ll Follow the Sun, and Candid Camera.

Southern California was experiencing a dry spell in early November. While not a full-blown drought, there was a lack of significant rainfall in the months prior. This left the vegetation in the hills extremely dry and vulnerable to fire.

On November 5, it was unseasonably hot in Southern California, with the mercury hovering up around 90 degrees Fahrenheit in Los Angeles. Violent hot Santa Ana winds toppled trees and utility poles, snapped power lines, shattered plate glass windows, and whipped up sandstorms that some people likened to the Dust Bowl.

The powerful gusts overturned a few vehicles, blew shingles off houses, threw walking bystanders to the ground, and caused traffic accidents across L.A. County, Orange County, and Riverside County. The Coast Guard warned that 60-mile-an-hour winds were making the ocean waters choppy off the coast, and one cabin cruiser with 17 people onboard was reported missing.

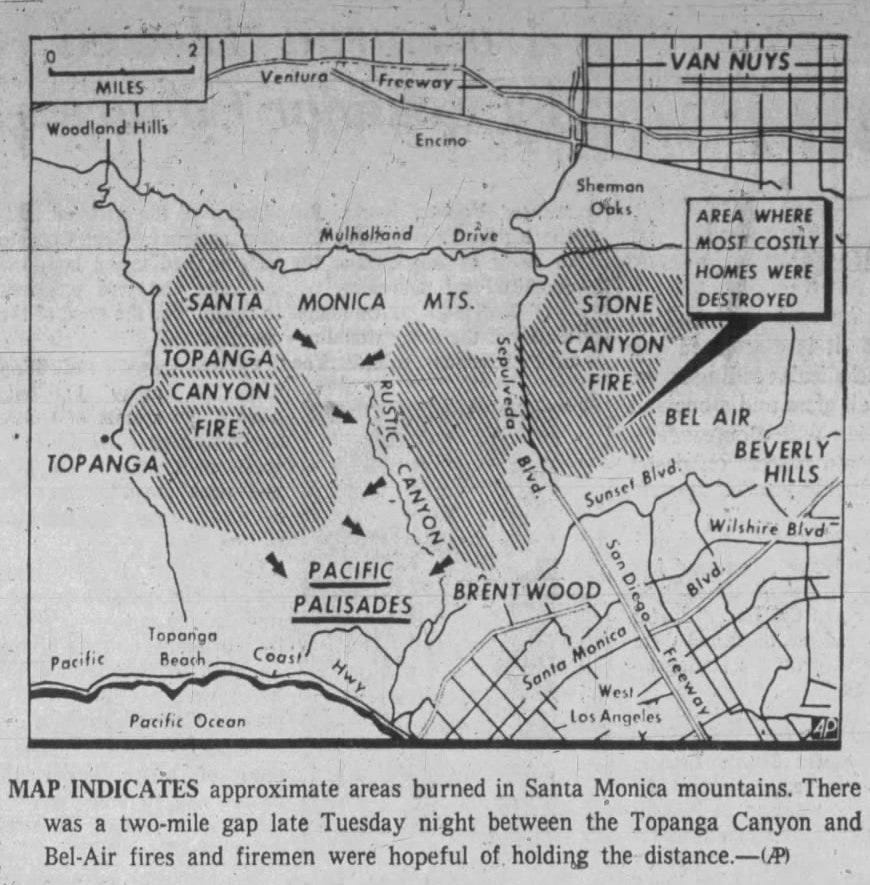

These winds also contributed to the enormity of the famous Bel Air Fire, which was really two fires. Most accounts pinpoint the beginning of the fire sometime around 8 a.m. on Monday, November 6, 1961, when a pair of fires erupted in the dry tinderbox brush in the Santa Monica Mountains. Howling windstorms whipped up flames and sent them spreading. Before long, giant clouds of dark smoke could be seen rising from the mountains above Los Angeles.[1]

On the western side of the Santa Monica range, the Topanga Canyon fire roared in the hills above Pacific Palisades and Malibu. To the east, the Stone Canyon fire leapt up to the skies and threatened homes nestled in the winding canyons. The two fires were separated by only about two miles.

Howling winds sent the fires on a wide swath, igniting acres and acres of dry brush and trees. The skies above the mountains darkened, blotting out the sun to a dull orange. Flames drew close in to the palatial homes of Bel Air, first imperiling the expensive dwellings along the winding roads of Stone Canyon, near a reservoir that bore the same name.

Fire companies – big and small – from all over Los Angeles County responded to alarm bells and alert calls. More than 2,500 firefighters in total battled flames, reinforced by support from over 300 police officers. Authorities evacuated 3,500 residents from different parts of Bel Air, Brentwood, and Pacific Palisades.

Frank Borden was a firefighter in his early twenties at the time of what he called the “Bel Air conflagration.” He worked at Fire Station (FS) 92 on Pico Boulevard, and he took pride in Engine 92, the station’s 1958 Seagrave engine. He described the morning of November 6 as “one of those days when you knew you were going to have some action.” The men of FS 92 witnessed the dark smoke rising from the Santa Monica Mountains and immediately suited up. With siren screaming, their engine roared out of the station and headed north toward the fire, packed with helmeted firefighters with no idea of what to expect.

The firetruck reached the edge of the blaze and the driver accelerated into the inferno, barrelling through swirling dark smoke and leaping flame. It came to a halt in the middle of a surreal smoky firestorm, with powerful winds blowing fiery shingles off the roofs of houses, which came raining down by the hundreds on the firefighters.

Frank and the other men of the company leapt off the truck and immediately went to work, moving into fire and smoke. At one point, Frank’s dungarees caught fire, which he had to put out with his gloved hand. All around him, houses belched flames out of windows and doorways, and structures collapsed into fiery ruins. Frank later recalled: “These houses were already burning blocks at a time, sending burning wood shingles into the air, transporting them by 50 MPH winds far ahead of the main fire.”[2]

Elsewhere, people began to evacuate their homes on the morning of November 6, among them movie stars, film directors, and other celebrities. But ordinary citizens who weren’t well-known also resided in the path of approaching fires. Fleets of school buses evacuated thousands of students who attended public schools located perilously close to one of the fires.

Former vice president Richard Nixon stood on his rooftop, using a garden hose to spray down the wood shingles at the top of the rented house in Bel Air where he lived with wife Pat and daughters Julie and Tricia. He stayed until the flames came within a few hundred yards of the house, at which point he evacuated with his family to a safe location. Luckily, firefighters were able to save his house, along with his family’s beloved cocker spaniel Checkers.

Comedian Joe E. Brown, known for his elastic Cheshire Cat grin and folksy demeanor, watched the fire close in on his house located on Bundy Drive, a peaceful wooded road above Sunset Boulevard. He left the scene before flames engulfed his house.

Brown later returned to search for any belongings that could be salvaged among the blackened ruins. He remained stoic when he told a reporter: “I miss my home. It was a wonderful place. A converted barn – it was done over in sort of a Mrs. Brown traditional. Now it’s gone and all the medals and trophies and mementos. I think my wife and I will buy a trailer.”[3]

The fires continued to spread during the day of November 6, destroying the homes of actor Burt Lancaster, actresses Joan Fontaine and Zsa Zsa Gabor, producer Walter Wanger, and CBS vice president Howard Meighan.

Zsa Zsa Gabor broke down and wept as she described the furs, jewelry, antiques, scrapbooks, and paintings – including original artwork by Picasso and Renoir – that were devoured by the fire. She took some solace that her gardener and house employees were able to save her three dogs. “I never dreamed that in such an elegant neighbourhood, in such a big city, that firemen could not control something like that.”[4]

Other local residents were spared from the ravages of giant flames. Narrowly missed were the homes of Marlon Brando, Alfred Hitchcock, Jack Lemmon, Shirley MacLaine, Maureen O’Hara, Greer Garson, Fred MacMurray, Bobby Darin, and Sandra Dee.

Whether a house was destroyed by the fire, or remained intact, depended entirely on the often-abrupt shifts in the volatile Santa Ana winds. There was a randomness about the destruction that conveyed the sheer power and force of nature. But once the flames descended from the hills, they ominously leapt across roads and walls and stormed through entire neighbourhoods.

A lot of homeowners defied evacuation orders and stayed at their houses as the flames neared. Their beloved dwellings contained everything they owned. Men and women waited in backyards, on decks and rooftops, and even indoors, peering out windows. Waiting. Hoping. Pacing fearfully. Some people hooked up garden houses and sprayed the edges of their property. Other residents would tearfully depart as flames entered their yards and spread to their houses.

At times, the winds whipped up terrifying firestorms that left observers feeling like they were standing in the middle of hell itself. A journalist described the surreal scene on that first day:

“Millions of smoldering embers lit up Chalon Road like a fairyland, and shadowy forms of residents and firemen could be seen moving through the blackened ruins. Massive gateways that once led to fabulous estates today led only to grim blackened ruins. A child’s blue toy wagon stood absolutely undamaged beside a gutted home on Chalon Road.”[5]

Firefighters performed the Herculean task of trying to contain, and eventually control, the fires. Arriving at the scene, they marched straight into hellscapes of immense orange flames and black smoke and burning embers. Reinforcements were trucked in from all over Los Angeles County. Aging B-17 bombers fitted with giant tanks of borate solution roared low over the fires, releasing giant payloads of fire retardants.

Some big red pumper trucks drew water from swimming pools to unleash their powerful spray on the encroaching blaze. In the hills above Pacific Palisades, men with flame throwers scorched wide rings of dry brush with flames in so-called “controlled fires,” and then abruptly put out the fires and used bulldozers to carve wide dirt fire breaks into the earth to halt approaching fires.[6]

The Los Angeles Fire Department established evacuation centers in the spacious gymnasiums of several public schools, where nervous men, women and children listened to transistor radios and awaited updates. Meantime, volunteer crews from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) and the West Los Angeles Shelter – responding to countless calls from panicked citizens worried about their pets – drove into the hills to rescue as many animals as they could with the support of firefighters.[7]

Black-and-white Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) prowl cars cruised the streets under dark clouds of smoke, remaining on high alert, intercepting a constant stream of two-way radio alerts. By the second day of the fire, Tuesday, November 7, the LAPD had established checkpoints all along roads going in and out of the fire zone. As one journalist noted: “The hills, which jut like a thumb into the Los Angeles basin, separating the San Fernando Valley from the rest of the city, were sealed off Tuesday by an army of police on guard to prevent looting.”[8]

By nightfall, eerie orange glows from the wildfires could be seen from miles away.

This fascinating aerial footage of the Bel Air fire from Los Angeles television station KTLA Channel 5 was shown on the channel’s news broadcast on the evening of November 6, 1961.

Such fires were nothing new to the Santa Monica Mountains. Older residents who watched the smoke rising north of Topanga Canyon recalled huge fires blazing through the area in 1938, 1956, and again in 1958. The Thanksgiving Day fire of ’38 was particularly ominous, spreading rapidly toward the Pacific Coast Highway and the oceanside Malibu colony to the west. It ultimately destroyed around 350 homes, everything from rustic log cabins to sprawling movie star mansions.

But this fire was different – the winds whipped harder, making it more ominous – and it threatened to consume large portions of the Santa Monica Mountains. Gene Hackley, a photojournalist with the Los Angeles Mirror, went riding in a helicopter and reported back to readers of the newspaper that it was “like a visit to Hades.” Despite being a photographer, he used words to capture the unforgettable inferno he witnessed:

“Flames leaped as high as 200 feet in the air from the brush-covered slopes. Frequently we could see the flames touch houses, but the smoke spread so quickly that we couldn’t tell how badly they were damaged. A ghostly light covers the whole area. The winds whip around from every point of the compass, turning flames now this way, now that.”

At one point during Hackley’s trip, the 70 mile per hour winds buffeted the helicopter he was in, sending it bouncing up and down like a toy, and “almost flipped us over.”[9] The helicopter climbed above the high winds, thousands of feet into the sky, giving Hackley and his fellow passengers a higher view of the gargantuan fires in the Santa Monica Mountains. For Hackley, the flight turned out to be a profound lesson about the awesome power of nature.

By Wednesday, November 8, firefighters had contained the Bel Air fires raging in the mountains above Los Angeles. That afternoon, tanker planes flew 100 sorties over the fires, dumping more than 200,000 gallons of borate solution, which doused flames. Firefighters went on the offensive in the canyons and on the high winding mountain roads, selflessly battling the flames and protecting houses.

Only a handful of stubborn “trouble spots” still burned by Thursday, November 9. The Santa Ana winds had slowed, temperatures began to drop, and the vast clouds of smoke had dissipated in the skies above the mountains. Three days of unrelenting brushfires left firefighters exhausted by the time it was brought under control.

This 1978 television documentary titled When Havoc Struck: The Bel Air Fire, narrated by actor Glenn Ford, uses a mix of dramatic footage and gripping interviews (including Zsa Zsa Gabor, whose house was destroyed in the fire) to tell the story of the massive inferno 17 years earlier. At only 25 minutes, it is worth watching for an informative overview of the fire.

The Bel Air fire proved to be the financially costliest fire in California history up to that point, eclipsing the fires ignited by the destructive San Francisco earthquake of 1906.[10] The fires destroyed around 500 structures, but miraculously did not claim any lives, thanks to the quick and decisive evacuation of the area by authorities. The source of the fire was never determined, and investigators found no evidence of arson.

In the aftermath of the Bel Air fire, city and county officials introduced significant changes in fire safety regulations in Los Angeles. The fire’s widespread destruction, fueled in part by the wooden shingle roofs common in the area, resulted in safety reforms that included a ban on wood shingle roofs in new construction.

Moreover, the fire highlighted the importance of brush clearance around homes, which became an important element of property maintenance in Los Angeles during the 1960s. The event also prompted increased public awareness about fire safety and the importance of individual responsibility in preventing wildfires.

Advancements in firefighting techniques and improvements in equipment followed the Bel Air fire. Agencies engaged in more effective coordination, improved communication systems, and eventually borate solution – hundreds of thousands of gallons of which was dumped on the wildfires in November 1961 – was banned due to its negative effects on animals and the environment.

Harrowing Universal-International newsreel footage of the Bel Air fire from November 1961.

The concept of climate change as we understand it today was not prominent in public discourse in 1961. While scientists were studying climate patterns and the potential impact of human activities on them, it wasn't yet the widespread concern it is now. And it was not on most ordinary people’s radar at the time. So, while the Bel Air Fire sparked public discussions about fire prevention and urban planning, it did not lead to a major debate about climate change's role in wildfires.

Moreover, the political climate surrounding natural disasters was different in 1961. While there were certainly political debates about how to respond to the fire and the best way to allocate resources, the political response to the fire was not as intensely polarized as it is today. The fire in 1961 was seen by politicians and the public alike as a shared tragedy, with an emphasis placed on the need for unity and cooperation in the face of disaster, rather than acrimonious finger-pointing.

The film Design for Disaster (1962), produced by the Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD), narrated by actor William Conrad, featured dramatic footage of the November 1961 Bel Air fire. The LAFD made the film hoping that it would educate the public about the dangers of wildfires and the need for fire safety awareness.

In general, people in 1961 tended to be much more optimistic about the future than they are today. They hoped that if the citizens of the future learned from the mistakes of the past, that disasters like the Bel Air fire could be avoided. That’s why the Los Angeles City Fire Department produced a compelling documentary called Design for Disaster, narrated by deep-voiced actor William Conrad, which contained important information about the fires of November 1961.

Little did the survivors of that giant, harrowing inferno in the fall of 1961 know that much worse conflagrations lay ahead.

NOTES

[1] An article headlined, “Thousands Fight Fires in Canyons” in the Long Beach Independent, November 8, 1961 (on page 4), identified the start time of the fires as Monday morning, November 6, 1961.

[2] For Frank Borden’s harrowing account, see “LAFD History – The Bel Air Fire, November 6, 1961,” on the Los Angeles Fireman’s Relief Association. URL: https://www.lafra.org/lafd-history-bel-air-fire-november-6-1961/

[3] “Mementos All Gone for Joe E. Brown,” Long Beach Independent, November 8, 1961, 1.

[4] “Losses Bewilder Sobbing Zsa Zsa,” Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, November 7, 1961, 2.

[5] “Proud Bel-Air Turned Into Charred Ruins,” Los Angeles Mirror, November 7, 1961, 2.

[6] “Palisades Area Still Threatened,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, November 8, 1961, 1.

[7] “Animals Die By Hundreds in Holocaust,” Los Angeles Mirror, November 7, 1961, 2.

[8] “Thousands Fight Fire in Canyons,” Long Beach Independent, November 8, 1961, 4.

[9] Gene Hackley, “‘Like Hades’ From the Air,” Los Angeles Mirror, November 6, 1961, 4.

[10] Carl Plain, “Bel-Air Fire Loss Seen at $25 Million,” Daily News-Post (Monrovia, California), November 21, 1961, 5.